芥子45期-The Great Compassion: Thomas Merton in Asia (Jack Downey)

The Great Compassion: Thomas Merton in Asia

大悲咒 - 多瑪斯•牟敦在亞洲

Jack Downey

In late August 2014, the Buddhist Peace Fellowship (BPF) held its first in-person community gathering since 2006, in Oakland, California. Founded in 1978 as a largely U.S.-based nonsectarian "Engaged Buddhist" network responding to U.S. militarism and nuclear proliferation, BPF now orients itself within an intersectional framework that seeks to critically push back against contemporary structural and interpersonal manifestations of colonialism, misogyny, racism, worker exploitation, and bigotry through practices of mindfulness and "compassionate confrontation." One of the plenary speakers, Larry Yang – a distinguished Dharma teacher and co-founder of the East Bay Meditation Center – began his talk on "beloved community" with a quote from Thomas Merton's Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander:

[T]here is a pervasive form of contemporary violence to which the idealist fighting for peace by nonviolent methods most easily succumbs: activists and overwork. The rush and pressure of modern life are a form, perhaps the most common form, of its innate violence. To allow oneself to be carried away by a multitude of conflicting concerns, to surrender to too many demands, to commit oneself to too many projects, to want to help everyone in everything is to succumb to violence. More than that, it is cooperation in violence. The frenzy of the activists neutralizes his work for peace. It destroys his own inner capacity for peace. It destroys the fruitfulness of his own work, because it kills the root of inner wisdom which makes work fruitful.1

That the reflections of a Catholic monk might be invoked at the outset of a Buddhist Dharma talk would be a profoundly peculiar proposition, were that monk almost anyone besides Thomas Merton. Particularly within "Americanist" Buddhist circles, Merton has essentially been adopted as an "anonymous Buddhist" – to borrow and potentially abuse a trope from the great twentieth-century theologian Karl Rahner, SJ.2 This theological anonymity would distinguish him from a confessing Buddhist, or a self-conscious agent of what has come to be known in Christian comparative theology circles as "multiple religious belonging."3 Merton was clearly a sincere student of Buddhism, as he was of many non-Christian religions – which is not to say completely unproblematic from the perspective of postcolonial anxieties about Christian spiritual appropriation (perhaps an impossibility). Unlike fellow Benedictines Henri le Saux, OSB (also known as Swami Abhishiktananda, 1910-1973, who helped found Saccidananda Ashram in 1950, in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, India, and devoted his life to Hindu-Christian "double belonging) or Bede Griffiths, OSB (Swami Dayananda, 1906-1993), who succeeded him – Thomas Merton's sudden death in 1968 interrupted his experiential foray into spiritual hybridity when it was still in its infancy, frustrating later theoretical interests in mapping him within the modern Catholic interfaith landscape.

But notwithstanding his appeal to Christian spirituality and the self- reflective project of academic comparative theology (of which he may have been – along with Abhishiktananda – source material for reflection), Merton has also become an object of the Buddhist gaze and appropriation, sometimes depicted as one whose concentrated fascination with the Dharma during the latter decades of life represented a syncretic evolution in contemplative depth, through the rigid structures of institutions, towards a more non-conceptual, unattached, perennial freedom and truth. Occasionally such comparisons might verge on a problematic kind of Buddhist supercessionism – that, in his apparent movement towards Buddhism, Merton was "maturing" spiritually, and leaving the vacuous rigidity of Catholicism behind for the more ethereal realm of the Dharma. But thus, without ever formally pledging fidelity to any other faith, nor showing any real indication of having contemplated renouncing Christianity or changing his base affiliations, Thomas Merton has managed to become a shared hybrid commodity, intelligible – certainly lovable – yet somehow strange and, at times, remote.

Zen and the Making of a Celebrity Monk

Like many "convert" Buddhist sympathizers of his generation in the United States, Thomas Merton's primary mode of first encounter with Buddhism was largely literary.4 His early comparative interests in Buddhism were piqued in the late 1950s by Japanese Zen, most particularly the writings of Daisetz T. Suzuki (1870-1966), whose English translations were available in abundance at the time, and who exerted a considerable influence over Anglo Buddhism during this period, before the Immigration Act of 1965 made the United States a more hospitable host to denominational leaders, whose vocations were as diverse as internal pastoral care for immigrant Asian communities (some dating back to the mid-nineteenth century), evangelizing potential converts, bridging cultural gaps, and ecumenical dialogue.5 D.T. Suzuki, a lay student of the Rinzai Zen roshis Imakita Kosen (1816-1892) and his successor Soyen Shaku (1860-1919) – along with Alan Watts and the Beats – played a critical role in popularizing Zen in the United States during the '50s. A prolific letter writer, Merton initiated a correspondence with Suzuki, which led to a face-to-face meeting in New York City – Merton was given a three-day leave by his abbot – in the spring of 1964.6 Merton was deeply impressed by Suzuki's doctrinal freedom, his openness to encounter Christianity on its own terms, without apparent concern for potential destabilizing ramifications on his own Zen commitments.7 In Suzuki, and increasingly the Zen tradition as a whole – as he understood it – Merton witnessed a detachment from dogma and concomitant prioritizing of non-conceptual experience that bore temperamental similarities to the Desert Fathers and medieval mystics like Meister Eckhart:

In all that he tried to say, whether in familiar or in startling terms, Eckhart was trying to point to something that cannot be structured and cannot be contained within the limits of any system. He was not trying to construct a new dogmatic theology, but was trying to give expression to the great creative renewal of the mystical consciousness which was sweeping through the Rhineland and the Low Countries in his time . . . . Seen in relation to those Zen Masters on the other side of the earth who, like him, deliberately used extremely paradoxical expressions, we can detect in him the same kind of consciousness as theirs. Whatever Zen may be, however you define it, it is somehow there in Eckhart. But the way to see it is not first to define Zen and then apply the definition both to him and to the Japanese Zen Masters. The real way to study Zen is to penetrate the outer shell and taste the inner kernel which cannot be defined. Then one realizes in oneself the reality which is being talked about.8

In the Zen approach, Merton glimpsed something vital that he believed to be diminished and under decline in modern Catholic religious life, which had – in his estimation – become spiritually vapid in the face of hyper-rationality and organizational structure.9 Merton drew upon the church's wellspring of contemplative resources as an aspirational antidote to contemporary spiritual stagnation, but also upon foreign traditions, such as Buddhism – maybe most particularly Buddhism. Like many Western spiritual seekers of his historical moment, Thomas Merton was an earnest pilgrim – albeit one who operated within an inevitably swirling matrix of earnest good intentions and neocolonial presuppositions that rendered Asia an object of desire and spiritual longing.

Born in 1915, in the Catalonian region of Southern France, along the Pyrenees, Merton's semi-itinerant adolescence crisscrossed the Atlantic, before Merton – a convert to Catholicism – finally found a residential berth seemingly ill-suited to his cultivated cosmopolitan tastes: the Trappist Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, tucked away deep in the heart of Kentucky bourbon country. Not yet a U.S. citizen, Merton was catapulted to quasi-celebrity status following the publication of his acclaimed memoir The Seven Storey Mountain in 1949.10 The narrative mirrored the Augustinian template of youthful indiscretion and wavering, graciously redeemed through a process of spiritual purgation and conversion. Although he was still a novice monk in the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance, Br. Louis was now a famous renunciate, and a standard-bearer for postwar spiritual renewal. Thus, at the very outset of his monastic life, Thomas Merton tread precisely along the fine line that John of the Cross warned was most subtle and pernicious: the temptation of spiritual pride that comes with gaining reputation for holiness.11 Throughout the years, Merton would have a conflicted relationship with his own celebrity, feeling profoundly estranged from his early, jubilant, triumphalist monastic self, while being simultaneously indebted to it for establishing the causes and conditions for so much opportunity that distinguished his unique vocation from that of his more anonymous Trappist brothers.12

By any generic standards, but particularly for someone who had discerned a vocation to a cloistered life of prayer in community, Thomas Merton led an exceptionally "active" life. His political engagement – especially in the antiwar movement – from behind the walls of Our Lady of Gethsemani, are legend. He was a peer and confidant of epic twentieth-century icons of the Catholic Left, like Dorothy Day and the Berrigan brothers, and attempted to juggle his seemingly bifurcated impulses towards ever-deepening solitude with the urgency he felt to respond to the chaos of social injustice that threatened to consume the world outside the monastery. All of this fed into his parallel calling – as well as his monastery job – as an author, which both kept him in the public spotlight and conversely fed his abidingly expansive interests in life outside the walls. His insatiable curiosity and chronic intellectual restlessness inevitably also drew him past the initial enthusiasm which characterized the conclusion of The Seven Storey Mountain, and as Merton moved deeper into the Christian contemplative practices, he found himself called – like so many of his generation who didn't share his fidelity to the Trappist discipline – to look elsewhere for sources of inspiration and wisdom.

Tibetan Buddhism & The Western Gaze

In Merton's day, Tibetan Buddhism had not yet migrated to the West in any substantial way. At the time of his death, there were still no Tibetan Buddhist Dharma centers in either Europe or the Americas. The invasion of Tibet by Chinese military, beginning in the southeastern region of Kham in 1950, precipitated successive waves of refugees braving the Himalayas to seek refuge in more cordial environs.13 This process would amplify considerably following the Tibetan uprising in March of 1959, and the Dalai Lama's subsequent escape to India, which he would make his new home. Merton's pilgrim encounter with Tibetan Buddhism on its own turf – albeit "in exile" – occurred on the cusp of its transcontinental migration. But until the 1960s, Tibet had largely been relegated to the Western imagination, fueled by reports from a small cadre of adventuresome missionaries and explorers who had made the arduous trek into the Land of Snows. The ethereal remoteness of Tibetan Buddhism resonated with both the physical inaccessibility and harshness of its indigenous landscape, and its perceived esotericism was alternately represented as an authentic remnant of primitive, authentic Dharma, or a demonic corruption, depending on the hermeneutic predispositions and theological preoccupations of its beholders.14

The U.S. Tibetologist Donald Lopez has raised a postcolonial lens toward the mechanisms through which the idea of "Tibet" as a site of the Western imagination – a place of fantasy and desire – has ill-served the project of Tibetan cultural agency, and how that in turn undermines very real and pressing human rights concerns.15 If part of Edward Said's critique of classical "orientalism" was that it depicted the Middle East as primitive, barbaric, and violent, its contemporary Tibetan iteration imagines Tibet as also primitive, but pristine and "spiritual" – an ideal type of a less materialistic pre-modern consciousness rather than a real place, with real people, living full, complex, sometimes contradictory lives. While many Western stereotypes of Tibet are "positive" in the sense of being romantic and appealing to liberal sensibilities, they are nevertheless still dehumanizing, in that the production of "Exotica Tibet" comes, in some sense, at the expense of Tibetan subjectivity.16

Some Christian comparative theologians' critiques of the "multiple religious belonging frame" contain similar concerns, including what seems to be a near consensus that cafeteria-style spiritual tourism or shopping may verge on being predatory and demeaning (regardless of intent) . . . a critique to which one might easily imagine Merton sardonically nodding in assent. Indeed the term "multiple religious belonging" has itself been deconstructed and critiqued as evincing inherent Anglocentric prejudices, but also, conversely, that this linguistic skepticism is itself the product of such bias.17 Additionally, Christianity's – or any monotheism's – systematic theological claims to preeminent "singularity" raise the fundamental question of whether it is even compatible with the "multiple religious belonging" conceptual model.18 But among interfaith practitioners, evinced in Merton's own disparaging of "hippies" as just a bit facile, there emerges a shared conviction that the project of hybridity demands deep commitments, persistent rigor, and existential solidarity across traditions. This passage into untraveled territory, as Peter Phan contends, is a perilous, heroic vocation, "not unlike martyrdom."19 The ascetic discipline, it is argued, distinguishes the comparativists' work as serious, in contrast to the easily dismissed neocolonialist spiritual poaching of the "New Age" (with which they might be lumped by more "siege mentality" insulars) – a somewhat outdated term which is used as a pejorative bludgeon to mark the boundaries of ethical fidelity and culturally (not to mention theologically) responsible forms of receptivity.20

Europeans had ventured into Central Asia with some regularity beginning in the thirteenth century, but it was not until 1715 and 1716 that Roman Catholics crossed into the Tibetan Plateau in order to really study its intellectual and spiritual traditions – albeit with somewhat diverse motivations in understandably meager numbers, given the superabundance of practical obstacles. The Portuguese Jesuit Ippolito Desideri (1684-1733) became the first Catholic missionary to steep himself in the lifeworld of Tibetan Buddhists – a methodological precursor of contemporary comparativists, such as that modeled by Jesuit Francis X. Clooney's "deep learning" approach to linguistic and theological studies of Hinduism.21 Indeed, Desideri made such diligent study of Tibetan language that he was able to compose several texts – including an apologetic elucidation of the doctrine of the Trinity – in this adopted tongue. Desideri agonized over the ultimate fate of the Tibetans, and speculated as to the true nature and origins of their religious tradition:

One might well doubt whether Christianity was founded in these regions or whether some apostle came here long ago. Such suspicion may be reasonably grounded by a great many things in the Tibetan sect and religion that bear a great resemblance to the mysteries of our holy faith, to our ceremonies, institutions, ecclesiastical hierarchy, to the maxims and moral principles of our holy law, and to the rulers and teachings of Christian perfection.22

Desideri's initial hypothesis that Tibetan religious life might be a corrupted mutation of primitive, orthodox Christianity, explained its apparent aesthetic similarities and the Buddhists' general moral uprightness, but also deviant corruptions, such as the institution of the Dalai Lamas which Desideri viewed as a sinister hereditary dictatorship – possibly a sort of antipope engineered by Satan.23 Indeed, Desideri witnessed traces of the demonic permeating Tibetan "theocratic" politics, and throughout his half-decade living on the Plateau, seems to have possibly even deepened his Christocentric triumphalism along with a then-unprecedented Christian-Buddhist comparative aptitude. In Desideri's passage across the Himalayas, scholars may witness a harbinger of theological responses to the contemporary reality of religious pluralism, but also a window into the subjective experience of missionaries as they confronted indigenous cultures and contextualized them within an understanding of normative church teaching. As a scholarly ancestor of contemporary Tibetologists, cultural orientalists, ecumenists, and comparative theologians, Desideri has himself become an object of the fluctuating ideological projections of his interpreters, which occasionally dovetailed with well-traveled Jesuit romanticisms, as well as their concomitant antagonistic conspiracy theories.24

For early European missionary explorers such as Ippolito Desideri, the Tibet imaginary held fantastical promise as a hidden Christian remnant, or a spiritual battleground where a muscular Christendom might combat Satan and win souls for Christ. However, by the twentieth century, it had been absorbed into a larger framework of Buddhist-orientalism that looked to Asia for esoteric spiritual Vitality Greater exposure to non-western spirituality coupled with some postwar disillusionment opened optimistic supernaturalist seekers to the auspicious possibilities of Buddhism's stance on the precipice of globalization. Beat legends like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Alan Watts, and Gary Snyder became the popular face of Buddhism in the United States, as the culture expanded and hurtled towards a more psychedelic 1960s syncretism.25 But while successive generations of the counterculture may have been written off by mainline U.S. civil religionists as socially marginal dilettante dropouts, the sharp austerity of Zen resonated with a committed subset, who shared interests with a spiritually adventurous micro-community of Catholic ecumenists, such as Benedictine monastics like Dom Aelred Graham – the one-time abbot of Rhode Island's Portsmouth Abbey and author of Zen Catholicism (1963) who would decline a peritus invitation to Vatican II – and Thomas Merton.

A Trappist on the Road

Although in many instances differing wildly in theological temperament, commitment, and interpretation, Western (in this case meaning European and eventually U.S.) spiritual engagements with Asia rendered it an object of desire, a "cluster of promises" that surely would transform the subjectivity of its beholders.26 Thomas Merton was certainly no exception to this, and over a decade of focused study and aspirational daydreaming about travel to Asia in person had augmented his characteristic self-deprecation and glibness with an ecstatic romanticism, vibrating at a frequency that oscillated between enthusiasm and disillusionment – apparently contradictory characteristics that his handler in northern India, Harold Talbott, would come to view as essential to Merton's basic disposition.27 While the proximate cause of his journey was to participate in a 1968 conference in Bangkok hosted by Aide à l'Implantation Monastique (AIM), Thailand – as part of a pan-Benedictine delegation, and on the invitation of the renowned Dom Jean Leclercq, OSB – Merton viewed the opportunity as more of a pilgrimage, and was eager to carve out space on both ends of the conference to steep himself in indigenous Asian spiritual life, in addition to preaching engagements at various regional Cistercian communities. As his Pan American flight soared westward towards Honolulu – his first stop – on October 15, 1968, Merton dramatized his pilgrimage in tectonic, almost messianic terms:

The moment of take-off was ecstatic. The dewy wing was suddenly covered with rivers of cold sweat running backward. The window wept jagged shining courses of tears. Joy. We left the ground – I with Christian mantras and a great sense of destiny, of being at last on my true way after years of waiting and wondering and fooling around. May I not come back without having settled the great affair. And found also the great compassion, mahakaruna. There was no mist this morning.28

Merton was enticed, not necessarily by the promise of "happiness," but rather that of insight and enlightenment.29 But as he travelled, he did so not as a purely passive empty vessel, but as one firmly rooted in his own contemplative lineage, and autodidactically conversant in a cornucopia of comparative mystical traditions.

Arriving in Bangkok, Merton eventually made his way to Kolkata, where he encountered Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939-1987) – the first in what would be a litany of highly-realized Tibetan masters Merton would visit with in India.30 Trungpa – who would go on to found the first Tibetan Buddhist center in the West (Samye Ling, in Scotland), and later founded what is now arguably the most extensive Western Dharma network, Shambhala International – remembered the encounter fondly: "We had dinner together, and we talked about spiritual materialism a lot. We drank many gin and tonics. I had the feeling that I was meeting an old friend, a genuine friend . . . . He was the first genuine person I met from the West."31 Serendipitously as it were, Trungpa was himself on the verge of a vital transformation experience. He was at that time on his way to Bhutan, where he would make a retreat said to have been previously frequented by Padmasambhava, a semi-mythical Indian yogi who is credited with introducing tantric Buddhism to Tibet.32 During his ten days of meditation in a cave, Trungpa would receive a gongter ("mind treasure") – a kind of transtemporal direct revelation from Padmasambhava – of the Sadhana of Mahamudra text, which marked a pivot-point in his understanding of his vocation towards spiritual renewal, and would liberate him from the confines of conventional Tibetan Buddhist structures.33 Trungpa was thus inspired to move to Europe and, eventually, the United States, where he first established communities in Colorado and Vermont, and assembled an eclectic community of students, which included Allen Ginsberg and Joni Mitchell.34 Trungpa's overlap with Merton would be viewed by some as a providential meeting-of-the-minds between two epic figures of their age, both on the verge of breaking through the exterior forms of their respective denominations, towards a deeper, more fundamental way ofbeing.35

Merton left Kolkata for New Delhi, where he rendezvoused with Harold Talbott – an American who had converted to Catholicism at Our Lady of Gethsemani a decade earlier, had developed strong ties to Aelred Graham, and was presently studying Buddhism directly under the Dalai Lama. Talbott was twenty-seven at the time, and had taken up residency in Dharamsala, the hillside town in Himachal Pradesh allocated for Tibetan refugee settlement by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1959, which subsequently evolved into the political and cultural center of the "Exile" community. Talbott had pre-scheduled Merton an audience with the Dalai Lama, which Talbott considered a phenomenal honor. However, Merton balked with a dismissive, "I've seen enough pontiffs." Merton did not, unlike Ippolito Desideri, ascribe demonic allegiances, but rather, projecting his deepest misgivings about institutional Catholicism, expected the Dalai Lama would be an elitist powerbroker, the pinnacle of the Tibetan bureaucracy. As Talbott recalled, this proposition piqued Merton's iconoclastic hackles: "He didn't trust organized religion and he didn't trust the big banana. He did not come to India to hang around the power-elite of an exiled central Asian Vatican."36 Despite Merton's dim expectations of spiritual aptitude within theTibetan institutional hierarchy, his misgivings seemed to dissolve almost immediately upon meeting the Dalai Lama, who – over the course of three audiences – engaged Merton in conversations about philosophy, Marxism and monasticism (which was to be Merton's topic of discussion at the upcoming Bangkok conference), ecumenism, and the rudimentary fundamentals of Buddhist meditative posture.37 As a third-party observer, Harold Talbott characterized the image as "Giottoesque" – a hyper-lucid, almost regal encounter between two deeply realized spiritual experts.38

If Thomas Merton was pleasantly surprised by his interviews with the Dalai Lama, his admiration for Tibetan spiritual depth only grew during subsequent interviews with thaumaturgic high lamas, such as Kalu Rinpoche and Chatral Rinpoche. In particular Chatral Rinpoche (b. 1913) – a lay master in the Dzogchen tradition – struck Merton very deeply: "If I were going to settle down with a Tibetan guru, I think Chatral would be the one I'd choose."39 Harold Talbott took

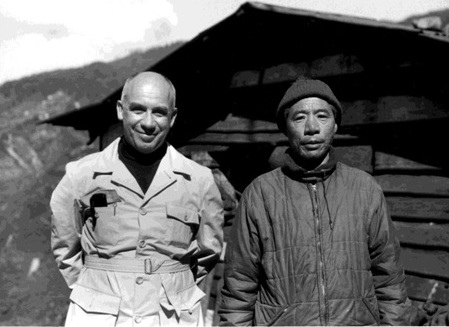

Merton with His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the

Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

Merton's affection for Chatral Rinpoche as evidence of his contemplative fortitude, for Talbott found Chatral absolutely terrifying – a living embodiment of the unpredictable, wild yogis that have historically augmented the more structured monasticism that is conventionally associated with Tibetan Buddhism. "He is savage about the ego," remarked Talbott.40 But Merton found him positively magnetic:

The unspoken or half-spoken message of the talk was our complete understanding of each other as people who were somehow on the edge of great realization and knew it and were trying, somehow or other, to go out and get lost in it – and that it was a grace for us to meet one another.41

The Dalai Lama had given Merton instruction on basic meditation techniques, and Chatral Rinpoche fired Merton's imagination by demonstrating the formative effects of a life dedicated to intensive practice. Although he had been introduced to the fundamentals of meditative training – shamatha (mental calm) and vipassana (insight) – by Rato Rinpoche in Dharamsala prior to his audiences with the Dalai Lama, Merton had been dismissively unimpressed, presuming to already have moved beyond remedial instruction.42 But the remainder of his pilgrimage more than convinced him that the Tibetan methodology produced real, exceptional, results – and Merton fantasized about delving further into the practice.43 As he prepared to continue his travels – to Sri Lanka, back to Thailand for the conference, and eventually, it was planned, to Japan – Merton was spiritually filled yet simultaneously unsated – analogous to Gregory of Nyssa's depiction of the beatific vision.44 He considered returning to India to establish a hermitage as a refuge from the bustle of life at Gethsemani – an impulse that had already prompted him to scout potential retreat sites in Alaska and the California Redwoods.

The mystical figure that had captured Thomas Merton's imagination and long-rendered Asia as an object of desire, seemed to deliver on its literary promise, which for several decades had been Merton's only real mode of access, which of course naturally limited him to the patchwork of whatever texts happened to be translated into English and were readily available in the U.S. market. Throughout his journals during this trip, Merton seems not at all preoccupied with speculation about the eternal destiny of heathen souls, nor for traces of the demonic. Rather, his self-image is as one of a pilgrim student, albeit – and quite understandably – not as a tabula rasa, but a supple and discerning disciple. Those familiar with Merton's style might find this hardly remarkable, but still it bears noting that this is before the promulgation of Vatican II's document Nostra Aetate, which officially recognized the intrinsic value of non-Christian religions, and set the stage for contemporary Catholic interfaith dialogue and comparative theology – at least from an official, doctrinaire church position. Merton was also on the front end of a generation that would commodify "Exotica Tibet," and read into Tibetan Buddhism a premodern, unsullied authenticity that he saw as redemptive for the materialist Western spirit. The operative conundrum was that it was precisely in the encounter with the West that Buddhism's messianic potential lay (at least for Westerners), but also – the tide flowing the opposite direction – the converse threat of the Dharma's "corruption." Thus, Merton could not help but adopt the posture of a cultural preservationist throughout his travels, wincing at signs of invasive western materialism, which he imagined as viral to dharmic purity.

Merton with Chatral Rinpoche

Used with permission of the Merton Legacy Trust and the

Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

"So Will I Disappear."45

Thomas Merton would have turned one-hundred this year. There was aturally much speculation about what loomed on the horizon, had he not perished unexpectedly. Rumors circulated that he was poised to leave Trappist life, to leave Christianity altogether, and convert full-tilt to Buddhism. However, there is no indication from his journals that such an event was in the works. On November 18, three weeks before his death, Merton reflected his relationship to Our Lady of Gethsemani, as he weighed his options, and dreamed about the future: "I suppose I ought eventually to end my days there. If I do in many ways miss it . . . . It is my monastery and being away has helped me see it in perspective and love it more."46 Methodologically, Merton might be said to have been at the vanguard of comparative theology and "multiple religious belonging," and embodied many of its complexities and implicit ambiguities, which have been elucidated considerably in recent decades, as ecumenism has grown increasingly complex and selfreflective.47 Ten years after Merton's pilgrimage to Asia, at the behest of what is now the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, the now-combined Benedictine commissions Dialogue Interreligieux Monastique/Monastic Interreligious Dialogue were founded in Europe and the United States, which has adopted a multi-pronged approach to interfaith practice that includes textual study, intellectual conversation, and residential exchange programs – practices that were modeled by Merton's own engagement with Buddhism.48 As a historical figure, Thomas Merton has been appropriated as an icon of contemporary ecumenism, but also of persistent orientalism, however sincere – a model of the "re-enchantment" turn towards esotericism and contemplative spirituality that augment a dim declension narrative of the stultifying effects of rigid institutional religion.49

Thomas Merton approached Buddhist Asia as a teacher, not a conquest. He was a sponge, albeit a critical and discriminating, sometimes judgmental, sponge (conscious of his ignorance, yet unable to abstain fully from exercising that ignorance) – which is not to ascribe anything sinister to his project. But the Dharma – as perhaps all objects of desire – remained elusive. Along with the cosmic flashes of insight, recognition, and transcendent compassion that he experienced with the Dalai Lama, and Chatral Rinpoche, and the apparently unimpressive "too-basic" instruction he received from Rato Rinpoche, there were occasions when his Tibetan meditation techniques seemed positively bizarre, almost alien. Upon arriving in Himachal Pradesh, prior to his meetings with the Dalai Lama, Harold Talbott jumpstarted Merton's whirlwind lama tour with visits to Khamtrul and Chokling Rinpoches, who both – quite to Merton's confusion – seemed most interested in giving him instruction in the unusual practice of phowa, a complex visualization practice that involves ejecting one's consciousness through a central meridian channel that passes through the cranium, thus simulating the migration of the soul from the body at physical death – a liminal period, when one has the opportunity to circumvent the round of karmic death and rebirth that conventionally condition creaturely existence, and occasion the persistent suffering of reincarnation. This practice is unusual, even among relatively seasoned meditators, and Merton found it, understandably, peculiar. Following his meeting with Khamtrul Rinpoche, Merton chronicled the experience: "We [Merton and Khamtrul] discussed the 'direct realization' method, including some curious stuff about working the soul of a dead man out of its body with complete liberation after death – through small holes in the skull or a place where the skin is blown off – weird!"50

However, Thomas Merton would, in fact, be dead within a month –electrocuted as he got out of the shower and killed instantaneously in his conference apartment back in Bangkok, on December 10, just minutes after delivering his conference talk. Harold Talbott and others would reinterpret the apparently arbitrary phowa sessions as corroboration of Khamtrul and Chokling Rinpoches' shared clairvoyance.51 Thus, in death, Thomas Merton was actually conscripted by Buddhism as confirmation of its own authenticity. Although one ought not overplay the transcendent import of Merton throughout the Buddhist community at large, over the years occasional speculation surfaced that he had been reborn in Asia as a budding monk or solitary yogi, and might even be – this very moment – stowed away in a Himalayan cave, deeply absorbed in some advanced meditative practice.52 Thus did Merton himself finally become an object of Buddhist desire, being appropriated by – rather than appropriating – Buddhism. It was a fitting, if somewhat billowy, epitaph for the perennially restless pilgrim whose final month of life was an intensive- yet-concise exercise in the inherently ambiguous and murky project of exploratory immersion in Buddhist waters, all the while remaining existentially tethered to the black and white of his Trappist habit.

Jack Downey is Assistant Professor of Religion and Director of Catholic Studies at La Salle University. He is the author of the recently published The Bread of the Strong: Lacouturisme and the Folly of the Cross, 1910-1985, published by Fordham University Press. For further comment on this article please contact the author: downeyj@lasalle.edu.

1. Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966), 73.

2. Karl Rahner, "Why Doing Theology Is So Difficult," interviewed by Karl-Heinz Weger and Hildegard Lüning (March 19, 1979) in Karl Rahner in Dialogue: Conversations and Interviews, 1965 -1982, edited by Paul Imhof and Hubert Biallowons, translated by Harvey D. Egan (New York: Crossroad, 1986), 218-219.

3. Raimon Panikkar, "On Christian Identity: Who Is a Christian?" in Many Mansions?: Multiple Religious Belon ging and Christian Identity (Eugene, OR: Wipf andStock, 2010), 126-127.

4. Richard Hughes Seager, Buddhism in America (New York; Columbia University Press, 1999), 15-16.

Seager identifies three fundamental categories of Buddhists in his study. The first, largely Chinese and Japanese, are descended from early immigrants to the United States, have lived for four or five successive generations as "Americans." Secondly are more recent immigrants/refugees who have entered the U.S. since the 1960s. Last, are non-ethnic Buddhists, or "converts." I use the term "convert" here following Seager's threefold typology, not simply to denote individuals who have only formally adopted Buddhism as their religious faith (converted in the strict sense), but rather to more broadly include those who have, in some way "turned their heart and mind towards… the teachings of the Buddha." Thomas Merton's influence has been, perhaps unsurprisingly, most influential over this latter demographic, of which he is also a member.

5. Christopher Queen and Duncan Ryuken Williams, American Buddhism: Methods and Findings in Recent Scholarship (New York: Routledge, 1999), 76.

The writings of D. T. Suzuki (along with his public lectures) have had a profound influence on some Americans since the 1940s, including his An Introduction to Zen Buddhism (1934), a book that continued to sell 10,000 copies each year in the 1990s. Suzuki's influence on sympathizers was both direct and indirect. His indirect influence came through the painters, musicians, therapists, and poets his books inspired.

See also: Thomas Tweed, The American Encounter with Buddhism, 1844-1912: Victorian Culture and the Limits of Dissent (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1992), 158. Iris Chang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 265.

6. Paul Elie, The Life You Save May Be Your Own (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), 368.

7. Richard Hughes Seager, Buddhism in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 49.

8. Thomas Merton, Zen and the Birds of Appetite (New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation, 1968), 13.

9. Massimo Faggioli, Vatican II: The Battle for Meaning (New York: Paulist Press, 2012); Gabriel Flynn and P.D. Murray, eds., Ressourcement: A Movement for Renewal in Twentieth-Century Catholic Theology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Jürgen Mettepenningen, Nouvelle Théologie – New Theology: Inheritor of Modernism, Precursor of Vatican II (New York: T & T Clark, 2010).

10. Thomas Merton, The Seven Storey Mountain (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1948).

11. John of the Cross, The Dark Night of the Soul 1.2.2-4 in The Collected Works of St. John of the Cross, edited by Kieran Kavanaugh, OCD and Otilio Rodriguez, OCD (Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1979), 363.

12. Thomas Merton, "June 13" in The Sign of Jonas (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1953), 328. [E]very day is the same for me because I have become very different from what I used to be. The man who began this journal is dead, just as the man who finished The Seven Storey Mountain when this journal began was also dead, and what is more the man who was the central figure in The Seven Storey Mountain was dead over and over. And now that all these men are dead, it is sufficient for me to say so on paper and I think I willhave ended up by forgetting them . . . . The Seven Storey Mountain is the work of a man I never even heard of. And this journal is getting to be the production of somebody to whom I have never had the dishonor of an introduction.

13. Tsering Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 32.

14. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 10.

15. Donald S. Lopez, Jr. "Foreigners at the Lama's Feet," Curators of the Buddha: The Study of Buddhism under Colonialism, edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1995), 251-296. See also Prisoners of Shangri-La.

16. Dibyesh Anand, Geopolitical Exotica: Tibet in Western Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 37-38.

17. Peter C. Phan, "Multiple Religious Belonging: Opportunities and Challenges for Theology and Church," Theological Studies 64 (2003): 498-499; Michelle Voss Roberts, "Religious Belonging and the Multiple," Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 26 (Spring 2010): 46.

18. Phan, "Multiple Religious Belonging," 499

19. Peter C. Phan, Being Religious Interreligiously (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2004), 81.

20. Catherine Cornille, "Introduction: The Dynamics of Multiple Belonging" in Many Mansions?: Multiple Religious Belonging and Christian Identity, edited by Catherine Cornille (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2010), 3-4.

21. Francis X. Clooney, SJ, Comparative Theology: Deep Learning Across Religious Borders (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 18.

[A]s I learned more of the Hindu tradition and more of my Christian tradition in light of Hinduism, I found myself all the more confident that going deep into both of them together – sent as it were from the one to the other, then back again – created the possibility of a deep and clear interreligious learning, insight arising through the chemistry of Hindu and Christian wisdoms in encounter.

See also: Donald S. Lopez, Jr., "Foreigners at the Lama's Feet": 254.

22. Ippolito Desideri, SJ, I Missionari italiani nel Tibet e nel Nepal 6, 297 in Trent Pomplun, Jesuit on the Roof of the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 78.

23. Pomplun, 122-123.

24. Ibid., 5-6. In the following passage, Pomplun casts a critical gaze towards the Desideri-as-proto- orientalist hermeneutic that he sees exemplified in Donald Lopez's work. This is, however, not an outright dismissal of Lopez's treatment of Desideri, which, on the whole, Pomplun finally exonerates.

In Lopez's telling, Ippolito Desideri becomes the sum and surrogate of our own anxieties,a cipher, or a mirror in which we might see our own fantasies reflected. The missionary's entry into the Tibeto-Mongol court in Lhasa is one among "several emblematic moments in which foreigners positioned themselves before Tibetan lamas, sometimes standing, sometimes sitting, moments to which the present-day scholar of Tibetan Buddhism is inevitably heir." The missionary cannot but be victim and proponent of a violence that represents his Tibetan interlocutors in terms that foreshadow the modern Orientalist, who looks upon the past with nostalgia and his present interlocutors with contempt . . . . This should not take away from the lasting value of Lopez's work; indeed, it should serve as its confirmation. One cannot deny the missionary zeal coursing through Desideri's writings, nor the urgency born of it. But neither can one deny that Lopez is caught in some strange – yet strangely familiar – fantasies about Roman Catholics.

25. Rick Fields. How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1992), 248.

The spiritual atmosphere of the new generation was eclectic, visionary, polytheistic, ecstatic and defiantly devotional. The paper of the new vision, The San Francisco Oracle, exploded into a vast rainbow that included everything in one great Whitmanesque blaze of light and camaraderie. American Indians, Shiva, Kali, Buddha, Tarot, Astrology, Saint Francis, Zen and Tantra all combined to see fifty thousand copies on streets that were suddenly teeming with people . . . . The beats had dressed in existential black-andblue; this new generation wore plumage and beads and feathers worthy of the most flaming tropical birds. If the previous generation had been gloomy atheists attracted to Zen by iconoclastic directives – "If you meet the Buddha, kill him!" – these new kids were, as Gary Snyder told Dom Aelred Graham in an interview in Kyoto, "unabashedly religious. They love to talk about God or Christ or Vishnu or Shiva."

26. Lauren Berlant, "Cruel Optimism" in Cruel Optimism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 23-24.

All attachments are optimistic. When we talk about an object of desire, we are really talking about a cluster of promises we want someone or something to make to us and make possible for us. This cluster of promises could seem embedded in a person, a thing, an institution, a text, a norm, a bunch of cells, smells, a good idea – whatever. To phrase "the object of desire" as a cluster of promises is to allow us to encounter what's incoherent or enigmatic in our attachments, not as confirmation of our irrationality but as an explanation of our sense of our endurance in the object, insofar as proximity to the object means proximity to the cluster of things that the object promises, some of which may be clear to us and good for us while others, not so much. Thus attachments do not all feel optimistic: one might dread, for example, returning to a scene of hunger, or longing, or the slapstick reiteration of a lover's or parent's predictable distortions. But being drawn to return to the scene where the object hovers in its potentialities is the operation of optimism as an affective form. In optimism, the subject leans toward promises contained within the present moment of the encounter with her object.

27. Helen Tworkov, "The Jesus Lama: Thomas Merton in the Himalayas, an interview with Harold Talbott," Tricycle: The Buddhist Review (Summer 1992): 14-24.

See also: Bonnie B. Thurston, "Unfolding of a New World: Thomas Merton & Buddhism" in Merton & Buddhism: Wisdom, Emptiness & Everyday Mind, edited by Bonnie B. Thurston (Louisville, KY: Fons Vitae, 2007), 15-30.

28. Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1973), 4.

29. Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 24.

30. Merton, Asian Journals, 30 (October 20).

31. Chögyam Trungpa, The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Three, edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2003), 477.

32. Fields, 301. See also Fabrice Midal, Chögyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision

33. Chögyam Trungpa, "The Sadhana of Mahamudra: Selections from a Tantric Liturgy" in The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five, edited by Carolyn Rose Gimian (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2004), 303-309. See also: Judith Simmer-Brown, "The Liberty that Nobody Can Touch: Thomas Merton Meets Tibetan Buddhism" in Merton & Buddhism, 59-61.

34. For more on Trungpa's life, see Midal, Chögyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision; Chögyam Trungpa, Born in Tibet (Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications, 1977); Stephen T. Butterfield, The Double Mirror: A Skeptical Journey into Buddhist Tantra (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 1994); Diana J. Mukpo, Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa (Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2006).

35. Midal, 68-69.

36. Harold Talbott interviewed by Helen Tworkov, "The Jesus Lama: Thomas Merton in the Himalayas," 17.

37. Merton, The Asian Journals, 100-102.

The Dalai Lama is most impressive as a person. He is strong and alert, bigger than I expected (for some reason I thought he would be small). A very solid, energetic, generous, and warm person, very capably trying to handle enormous problems – none of which he mentioned directly. There was not a word of politics. The whole conversation was about religion and philosophy and especially ways of meditation. He said he was glad to see me, had heard a lot about me. I talked mostly of my own personal concerns, my interest in Tibetan mysticism. Some of what he replied was confidential and frank. In general he advised me to get a good base in Madhyamika philosophy (Nagarjuna and other authentic Indian sources) and to consult qualified Tibetan scholars, uniting study and practice. Dzogchen was good, he said, provided one had a sufficient grounding in metaphysics – or anyway Madhyamika, which is beyond metaphysics. One gets the impression that he is very sensitive about partial and distorted Western views of Tibetan mysticism and especially about popular myths. He himself offered to give me another audience the day after tomorrow and said he had some questions he wanted to ask me.

38. Talbott in Tworkov, 22.

39. Merton, The Asian Journals, 144.

40. Talbott in Tworkov, 24.

41. Merton, The Asian Journals, 143.

42. Simmer-Brown, 67.

43. Merton, The Asian Journals, 148.

I am still not able fully to appreciate what this exposure to Asia has meant. There has been so much – and yet also so little. I have only been here a month! It seems a long time since Bangkok and even since Delhi and Dharamsala. Meeting the Dalai Lama and the various Tibetans, lamas or "enlightened" laymen, has been the most significant thing of all, especially in the way we were able to communicate with one another and share an essentially spiritual experience of "Buddhism" which is also somehow in harmony with Christianity.

44. Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses 238-239, translated by Abraham Malherbe (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 116.

[N]o consideration will be given to anything enclosing infinite nature. It is not in the nature of what is unenclosed to be grasped. But every desire for the Good which is attracted to that ascend constantly expands as one progresses in pressing on to the Good. This truly is the vision of God: never to be satisfied in the desire to see him. But one must always, by looking at what he can see, rekindle his desire to see more. Thus, no limit would interrupt growth in the ascent to God, since no limit to the Good can be found nor is the increasing of desire for the Good brought to an end because it is satisfied.

45. Merton, The Asian Journal, 343. These are the very last words that Thomas Merton spoke at the end of his paper "Marxism and Monastic Perspectives" delivered in Bangkok on December 10, 1968. He would die shortly thereafter.

46. Merton, The Asian Journals, 149.

47. Phan, "Multiple Religious Belonging," 507.

48. Donald W. Mitchell and James A. Wiseman, The Gethsemani Encounter: A Dialogue on the Spiritual Life by Buddhist and Christian Monastics (New York: Continuum, 1997), xi-xii.

49. Jeffery Paine, Re-Enchantment: Tibetan Buddhism Comes to the West (W. W. Norton, 2004), 11.

50. Merton, The Asian Journals (November, 3), 89.

51. Talbott in Tworkov, 21.

The reason Chogling [sic] Rinpoche taught Merton phowa practice – say I – is that he saw that Merton was going to be dead in a couple of weeks. He needed the teachings on death. He did not need teachings of karma and suffering, calming the mind, insight meditation. He needed to be taught how to dispose his consciousness at the time of death because this was the time of death for him. And Merton scribbled in his journal: "I'm not sure about all this consciousness and shooting it out the top of the head. I'm not sure this is going to be very useful for us."

52. Simmer-Brown, 85.

(The article was published on AMERICAN CATHOLIC STUDIES Vol. 126, No. 2 (2015): 107-125)